Software development methodology is organizational Valtrex. Sure, it treats a symptom, but the only cure for the underlying disease is to never have contracted it in the first place. This is not to say that process and methodology are bad. They are means to an end. But the ability of your team to execute on a goal is inversely proportional to the amount of process you have in place. It's not a direct correlation, though. The underlying cause is that the variance of developer skill on your team is too high, which means your team can't execute well, and you need process to wrangle the laggards.

Software development methodology is organizational Valtrex. Sure, it treats a symptom, but the only cure for the underlying disease is to never have contracted it in the first place. This is not to say that process and methodology are bad. They are means to an end. But the ability of your team to execute on a goal is inversely proportional to the amount of process you have in place. It's not a direct correlation, though. The underlying cause is that the variance of developer skill on your team is too high, which means your team can't execute well, and you need process to wrangle the laggards.

Software development processes exist to manage the bell curve of ability in developers. It's simple mathematics. The more people you collect on a team, the more likely it is that the team's average skill is the average skill of software developers as a whole. This is the Strong Law of Large Numbers, and it is non-negotiable. There's not a meeting you can hold to make it go away. Most organizations simply accept their fate, and design policies and procedures to keep the back half of the bell curve from causing damage. Unfortunately, policies and procedures irritate top performers, and are just more grievances on their list that will some day metastasize into a resignation letter. (Side note: if someone keeps such a list, there's a high probability they are a top performer.)

So, how do you produce good software?

Rule 1: Resist Process from the Start

Anti-process needs to be in your blood from the beginning. Growing the team causes problems, but adding people who like to make process is catastrophic. Busybodies are toxic. When we were making Milo, the development process was, for a long time, loosely coordinated chaos. Of course this caused problems, and there are a few bodies in the codebase to prove it. When there was some big fuckup, a bunch of us would sit in a room (mistake 1), try to "trace the root" of the problem, which is code for "place blame" (mistake 2), and then figure out what process we need to put in place to make sure it never happens again (mistake 3).

Every time we tried to force process on the team, it failed, because process was not part of the corporate culture. Here's a concrete example:

Around the time we were raising our Series A financing, I was doing some maintenance work on our one and only database machine, Zeus. Because I had overconfigured Nagios, it was going apeshit as I was working, so I disabled all alerts for that machine. Sure enough, I forgot to re-enable alerts when I was done, and sure enough, that night, Zeus's RAID controller decided he'd had enough of our bullshit and up and died.

The site was down for 6 hours and nobody noticed because we were all asleep. Do all the root cause analysis you want on that one, I fucked up, and everyone knew it. We tried policy: don't ever disable Nagios alerts, just tell people when you're working on something so they know to ignore the alerts. But nobody followed the policy because homie don't play dat.

It turned out that nobody ever made that mistake ever again. Maybe it was just by chance, but maybe it's because of the Old Testament type stomping that the next person to do that would get.

Learn from your mistakes, but don't flagellate yourself with them.

Rule 2: Grow Headcount as a Last Resort

Headcount is not a virtue. Functionality is a virtue. Ability to execute is a virtue. But having a lot of people working on the project? No. It's a liability.

The Strong Law of Large Numbers burns you when the team grows, so be reluctant to grow the team. When you think there is too much work for your current team to handle, do what any good programmer does: profile. Quantify the amount of time your team spends on every task, then figure out what you can optimize.

When you do hire, do it carefully. Really carefully. ... More careful than that. At Milo, we do "trial periods", where we invite a candidate to work with us for a few days so we can judge their work. Here's a really simple trial period task: make this thing better. Use your judgment and your programming skills, just make it better. This will keep a common vision in your team.

Rule 3: Use The GitHub Workflow (And Other Good Stuff)

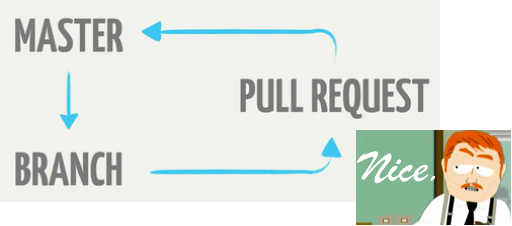

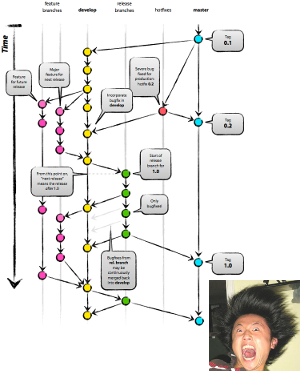

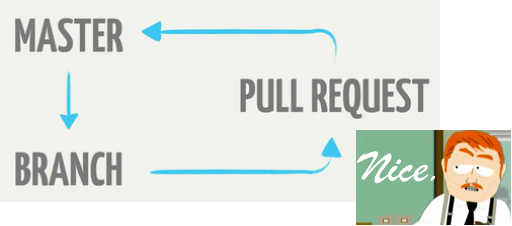

For brevity:

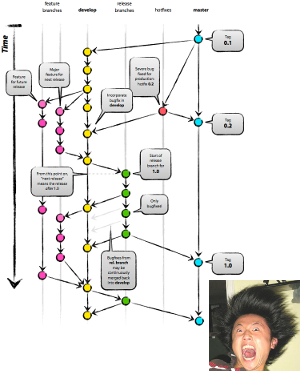

versus:

Seriously, what the fuck is going on in that branch model? Policy and procedure, that's what. We used the latter branch model at Milo, as GitHub was not yet ready enough to support their awesome workflow. That complicated but popular workflow is vicious, there is just too much state to track in your head as a developer. It's not something you need to spend your time on.

It's not specific to the GitHub workflow: your tooling should have the same attitude toward policy that your team does. GitHub's (the software, not the company) opinion is that process is unnecessary, and having the tools to support process will only beget process.

If you leave enough handguns hanging around, eventually someone's going to get shot.

If a tool is forcing process on you, or even encourages you to follow some process, ditch the tool and find another. Ticket tracker has a lot of fields on the ticket form? Dump it. Code review tool has a lot of shit going on? Find a new one. You get the idea. Don't let your tools infect you.

Rule 4: Just Let Go

This is the hardest one, and, if you're serious about doing away with process, is the one from which all others follow. Just stop having process. Cancel your weekly planning meetings. Get rid of your prioritized list of tasks. Stop having your daily stand-ups. No more status report e-mails.

Just stop doing that stuff, and get rid of anyone who can't cope.

Nothing terrible will happen.

My current project, which will be launching in the first half of 2012, is as close to anarchy as a project can get. And it's working. I trust my teammates to get their work done and do it well. Sure enough, they do.

Evidently Dan Lyons is on the warpath now, against MG Siegler and Mike Arrington, formerly of TechCrunch, now of CrunchFund. You remember Dan Lyons, he was entertaining for about five minutes a couple of years ago as Fake Steve Jobs? This sort of depraved cannibalism is common in Silicon Valley tech media, so it should surprise nobody.

Evidently Dan Lyons is on the warpath now, against MG Siegler and Mike Arrington, formerly of TechCrunch, now of CrunchFund. You remember Dan Lyons, he was entertaining for about five minutes a couple of years ago as Fake Steve Jobs? This sort of depraved cannibalism is common in Silicon Valley tech media, so it should surprise nobody.

Software development methodology is organizational Valtrex. Sure, it treats a symptom, but the only cure for the underlying disease is to never have contracted it in the first place. This is not to say that process and methodology are bad. They are means to an end. But the ability of your team to execute on a goal is inversely proportional to the amount of process you have in place. It's not a direct correlation, though. The underlying cause is that the variance of developer skill on your team is too high, which means your team can't execute well, and you need process to wrangle the laggards.

Software development methodology is organizational Valtrex. Sure, it treats a symptom, but the only cure for the underlying disease is to never have contracted it in the first place. This is not to say that process and methodology are bad. They are means to an end. But the ability of your team to execute on a goal is inversely proportional to the amount of process you have in place. It's not a direct correlation, though. The underlying cause is that the variance of developer skill on your team is too high, which means your team can't execute well, and you need process to wrangle the laggards.